Have you ever thought about writing down all those family stories that everyone has heard, but only few can recall all the details? Or researching a family member or ancestor who you feel particularly connected to or inspired by? If yes, writing about your family might be the perfect project for the holidays. (You can also commission me to do it!)

Writing and recording your family history is important to pass on stories to future generations. As a researcher, it helps you lay down everything you know, and then identify the gaps and further research questions or areas that you can focus on. If you’ve been researching your genealogy for a while, writing helps make sense of all the bits of information you’ve collected; if you haven’t, it gives you somewhere to begin. And finally, writing your family history makes it easier to share what you’ve found with other members of your family.

Whether you’ve been researching your ancestors for a while or you’re just getting started, here are some ideas to get the words flowing.

Brief biographies

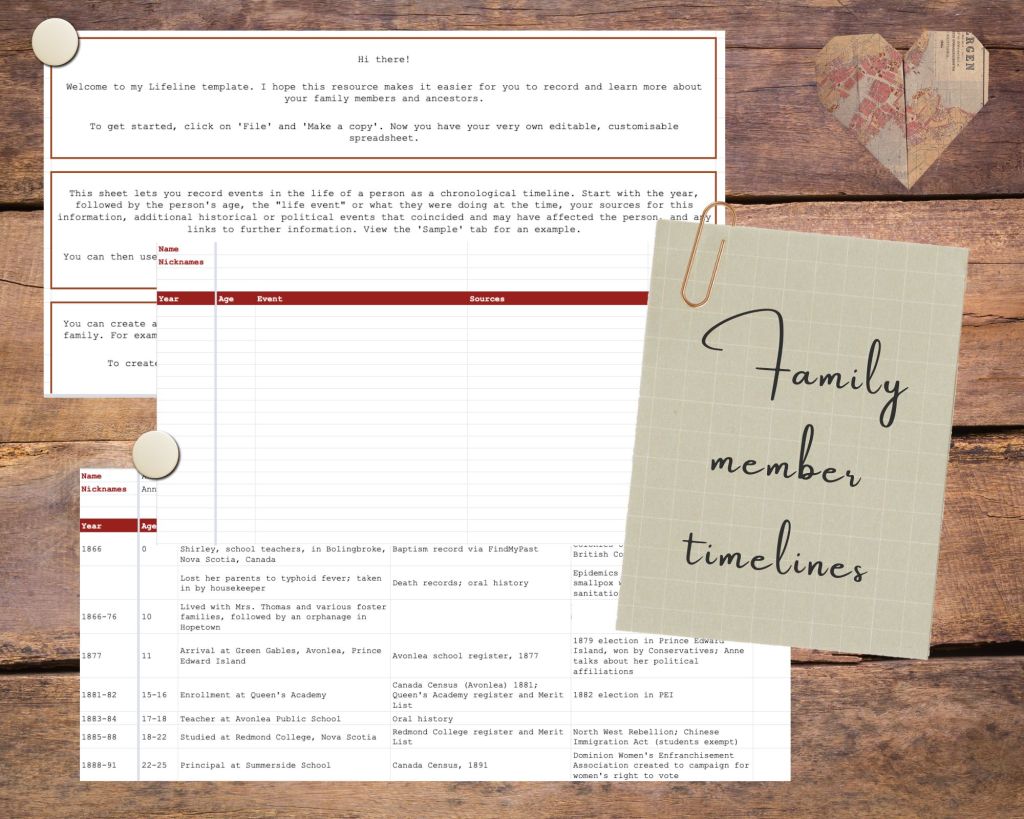

An easy way to get started is by focusing on various members of your family and recording their stories chronologically. You can use information from records, oral history, letters, photographs and more to piece together a life story. I like to first create a sheet for each person – a timeline of events during their lifespan, including information about parents and siblings, profession, marriage etc., as well as wider contexts of the time that might have affected or intersected with their lives. You can get my chronology template here or create your own.

These templates are helpful to keep track of your research, ask questions and add further information as it becomes available. Once I’ve completed the details I have access to, I write them in a biographical form, adding more narrative and information from other sources, such as my great-grandparents’ love for poetry and music that I came across through letters, photographs and oral history.

Oral (hi)stories

We’ve all sat down with our grandparents and heard their tales multiple times, but often, they’re not easy to recount. Before I started my genealogical research a few years ago, I would note down or record (with permission) these stories so that I could get the details right, but I wasn’t very organised about it.

I recently located some of these old notes and was astounded at how many little details I had forgotten that filled in the larger picture and added so much nuance. You may have the historical records of your great-grandmother’s birth or marriage, but you’ll only ever hear stories about her French convent education – where punishments meant being banished to the wine cellar – from people. Best write them down while they’re fresh.

Going places

Which places were especially significant to your ancestors? Where were your grandparents born? Where did they grow up, work, settle down? Perhaps they told you about their childhood home, the school, the fruit trees. Perhaps you read about their town in letters or saw it in photographs. Have you been there, or do you perhaps still live there? Weave in your impressions and learn about their history.

You can talk to other members of your family or their friends who lived nearby to add more colour. My great-aunt’s friend recently wrote to me describing their walk to school together and the long conversations they had under tamarind trees. If you don’t have access to many stories, turn to history books and other secondary sources such as maps and archival photographs which can provide an interesting image of what life might have been like for your ancestors in that place. For instance, I visited and wrote about the small town where my great-grandparents settled after retirement.

Painting contexts

Researching the historical and political events of the time and how they might have affected your ancestors can provide interesting insights and further stories. Was there an epidemic? A war? A protest? A technological advancement that was all the rage?

Secondary research can provide wider contexts, and you can ask your family more specific questions about these aspects to learn how they were impacted personally or as a community. For instance, many of my ancestors were directly impacted by the Partition of India, but in distinct ways – most of my Anglo-Indian family members migrated to other countries, while my grandparents who had a home in what is now Pakistan had to seek refuge in India. (All my writing packages include secondary research to add context to your stories.)

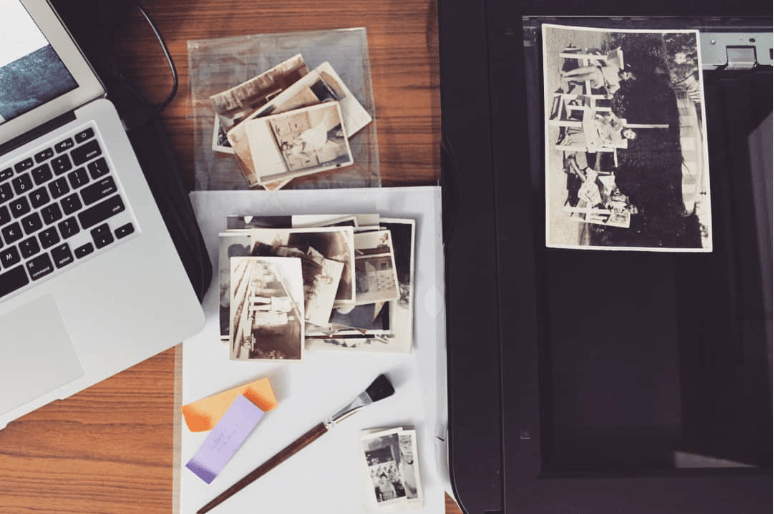

Reading photographs

Images can trigger all kinds of stories. Describing an image is a great writing exercise – you could elaborate on the people in the image and their relationship to each other, when and why the photograph might have been taken (e.g., a special occasion), where it was taken and what the backdrop or location looks like, the objects seen in the photograph, gestures and expressions, clothing and fashion, the type of camera or film or style used to make the image, and more.

It’s also interesting to think about who’s missing, for example, from a family photograph, and why that might be; or which objects were present in later photographs but hadn’t yet been acquired when the current photograph was taken.

Passages on travel

Don’t voyages sound adventurous? BMD (birth-marriage-death) records can give us clues as to whether someone lived their entire life in one place or relocated one or more times. If records are not available, photographs, postcards or letters might provide details about holidays and visits.

These can make for interesting stories – when and where did someone travel? What was the purpose of the visit? Did they go alone or with their family? Which mode of transportation did they use and what was the journey like at the time? Passenger lists showed me which members of my family undertook the long journey between India and the UK, which ships they were on, and their addresses and professions. Some of my great-grandfather’s letters tell me he enjoyed his travels but found them expensive and was happy to return home “where things are cheap, if nothing else”.

Tracking research

Finally, one of the most important types of writing when it comes to family history are detailed notes about your research process and findings, including sources and citations for a particular fact or story. After a while, research can feel like going down a rabbit hole and I often find myself getting lost. Writing helps unravel the strings and weave them all together.

It is also essential as a reference point – you will likely not remember how you found something a year ago, and having clear notes is vital to avoid researching the same things over and over again and finding references quickly. My Research and Activity Log is an easy way to keep track of your notes and sources, and a timeline of your research. I like to write down what I’ve found each time I delve in and pick up where I left off.

Commission me to write your family’s stories.

Shop my Family Member Chronology and Research and Activity Log here.

Sign up for my monthly newsletter and follow me on Instagram.

Leave a comment